Number of the Week: $32 billion (explanation below)

What PayPal’s Meltdown Means

The tech stock sector in early 2022 has been a bloodbath. This week, Facebook/Meta lost more value—$226 billion—in a single day of trading than any company in the history of American stock markets. Overall, the tech-heavy Nasdaq index had its worst month in January since COVID struck in early 2020.

But from FIN’s perspective, the most telling continuing plummet has been PayPal’s stock. Unlike Facebook/Meta, PayPal’s descent doesn’t seem to emanate too much from regulatory concern, although it is interesting that the company reported that it has booted 4.5 million accounts off its platform because they were “illegitimately created.”

PayPal’s February 2nd earnings call for Q4 ‘21 seems to have surprised many analysts and investors with its shift away from getting new users, and instead focusing on increasing the revenue it squeezes out of existing customers. As Mark Palmer of BTIG put it in a note downgrading PayPal to “neutral”:

One new area of uncertainty around PYPL’s story stems from management’s disclosure…of a significant shift in the company’s approach to customer acquisition and engagement. Another emerged when management said their FY22 forecast was cautious due in large part to exogenous issues – the impact of inflation on consumer spending and the effects of supply chain issues on their small-business customers – that offered a sharp contrast with the more upbeat annual outlooks offered recently by the card networks.

A couple of points here very slightly in PayPal’s defense: eliminating “illegitimate” users should benefit the company over time, even if it dents new user acquisition and gives Wall Street analysts chest pains. And, yes, PayPal’s explanation about “exogenous” factors is boilerplate that many companies issue when things go sour, plus PayPal has been saying such things at least as far back as July.

Still, this claim shouldn’t be immediately dismissed; indeed, it can be argued that PayPal’s last two years have been *all about* exogenous factors. Consider: PayPal’s stock is now trading at a price not far from where as it was at the very beginning of 2020, just before the pandemic became a force in the United States. A two-year horizon illuminates some key inflection points:

As COVID’s impact is first felt in late February 2020, PYPL gets hit just like everyone else. But fairly quickly, two things became apparent: 1) Contactless payments would become a lot more popular in a lockdown environment, and 2) Government stimulus would give people more money to spend through PayPal. A PYPL stock analyst this week aptly described COVID’s impact on PayPal stock as a “sugar rush.”

The rush endured for many heady months, but as the chart illustrates, whenever PayPal had to explain basic information—such as the expiration of some US stimulus in early 2021—its stock took an understandable hit.

But there are limits to the exogenous excuse; many of PayPal’s recent wounds are entirely self-inflicted. PayPal shareholders may be a glum gaggle right now, but how much worse would the company be if it had gone through with the proposed $45 billion purchase of Pinterest, floated in October? Similarly, the $2.7 billion purchase of Japan’s Paidy, at a price of more than 40 times projected earnings, always struck FIN as extravagant, despite defenses of it (that the deal was all in cash must especially sting today, when PayPal has a lot less cash to play with). The company also had to admit that it didn’t fully understand how swiftly eBay was going to move users away from PayPal to a different payment system. Finally, Palmer’s note included an especially troubling development: Venmo’s growth is slowing down.

Venmo, PYPL’s peer-to-peer payment app, posted total payment volume (TPV) of $60.6 bn during the quarter, missing the consensus estimate of $64.9 bn. While Venmo’s TPV increased sequentially from $60.0 bn in 3Q21, the app’s growth rate decelerated meaningfully.

PayPal—arguably the most important global fintech innovator of all time—has become bloated, distracted and kind of dumb, no longer in a position to innovate or even manage its internal operations especially well—how could the company be so wrong about the timing and impact of eBay’s plans? The COVID sugar rush masked this state of affairs, and of course the stock could still turn around over time. But it feels as if the next couple of years of PayPal will involve trying to plug holes, not create bold new market-seizing strategy.

Will Monzo Make a Splash in the US?

It’s hard to overstate how powerfully Monzo looms over the UK neobank landscape, particularly because its origin story is so closely interwoven with one of its largest competitors (the founding team had met while they were working at Starling bank). In 2016, Monzo (then called Mondo) legendarily raised one million pounds in 96 seconds via the crowdfunding site Crowdcube, crashing the site’s servers.

This week, Monzo’s US product came out of beta, a move that might have happened sooner if the company had succeeded in its efforts to obtain a US banking license. (Instead, Monzo offers US banking services through a partnership with Sutton Bank.)

Monzo claims a formidable 5 million user customer base in the UK, and has long sought to make a similar splash in the US. And in December 2021 the company hit two successful high notes. A fundraising round valued the company at $4.5 billion, and China’s titan Tencent announced it had taken ownership of a small percentage of Monzo.

Yet it’s hard to avoid the conclusion that Monzo is going to have an uphill climb in the US. Monzo continues to lose money. Monzo is under Financial Conduct Authority investigation for possible money-laundering violations. Plus, the US neobank market is already crowded and, as German neobank N26’s November decision to abandon the US hinted, is not especially hospitable to even the most successful foreign competitors. Maybe it’s too early to tell, but Monzo’s offerings don’t seem distinctive or attractive enough for the company to gain too much traction in the US.

Jack Dorsey’s BIzarre Bitcoin UBI Take

Perhaps no one—not even Square and Twitter cofounder Jack Dorsey—should be held accountable for things they say in the cacophony that is Twitter Spaces. Dorsey sounded a bit out of place in a live Spaces session on February 4, ostensibly devoted to Bitcoin and Universal Basic Income (UBI) but also a showcase for the Congressional campaign of Aarika Rhodes, a school teacher who is running a Democratic primary campaign against Congressional incumbent Brad Sherman, who represents the northern part of Los Angeles and nearby suburbs.

The conversation was especially disjointed, in part because Sherman—who sits on the House Financial Services committee—is widely considered to be Congress’s fiercest cryptocurrency foe. As a result, Rhodes’s largely left-of-center campaign is being supported by crypto enthusiasts who lean more toward libertarianism. Rhodes, it seems, is a recent convert to the charms of cryptocurrency and thus has attracted a lot of attention, including from Dorsey.

Any listeners expecting a discussion of how Bitcoin might be used to implement a UBI program were largely disappointed: for the most part, attendees who wanted to discuss UBI overlapped very little with those who wanted to discuss Bitcoin. About 25 minutes in, Dorsey was asked whether, given the skepticism that many Bitcoiners have for UBI, he thought that UBI was something that the US government and other governments should experiment with as a social safety net.

This was Dorsey’s response:

I’m skeptical of it as well. I’m skeptical of any government capital allocation. Certainly the amount of capital that we put into the Department of Defense is crazy, in comparison to actually trying to experiment to help people’s lives and get them through a pretty hefty transition from a lot of the mechanical work we find today to a more automated future, which is happening in nearly every industry, including software engineering. I think there are much better uses of money if we’re smarter about it, but the problem is we don’t have a lot of transparency. If the government were to run experiments, I doubt we’d get satisfactory transparency around what works and what doesn’t work.

This is a peculiar thing for Dorsey to say. After all, he has very publicly given tens of millions of dollars to support local government UBI experiments all across the country (and the world). In several cases, mayors have said that they would not have been able to get UBI pilot programs off the ground without Dorsey’s money.

Dorsey went on:

That’s one of the reasons I wanted to at least attempt to fund these myself, and work with others who are trying the same, so we can get as much data as possible. This has only been going on for about a year, it’s probably going to take more time to really understand what works and what doesn’t. But I definitely believe that the problem is large enough, that as many experiments as possible should be conducted. I don’t know that government is going to be the most efficient path to do that. So maybe creative, small experiments especially in newer ways such as utilizing Bitcoin and creating some closed-loop economies might be a lot more indicative of what we should consider, and what governments might actually want to put resources behind. Of course there’s exceptions, but I would say the more we can do more from the private standpoint to inform public policy, the better.

This is vague enough that presumably there are charitable interpretations, but it really does sound as if Dorsey thinks that if he is putting money into a government program, it is no longer a government program. And it *sort of* sounds like he is saying that the private sector would get behind UBI if only it were administered via Bitcoin—a pretty debatable assumption, even for Twitter Spaces.

Embedded Finance Is Further Along Than You Thought

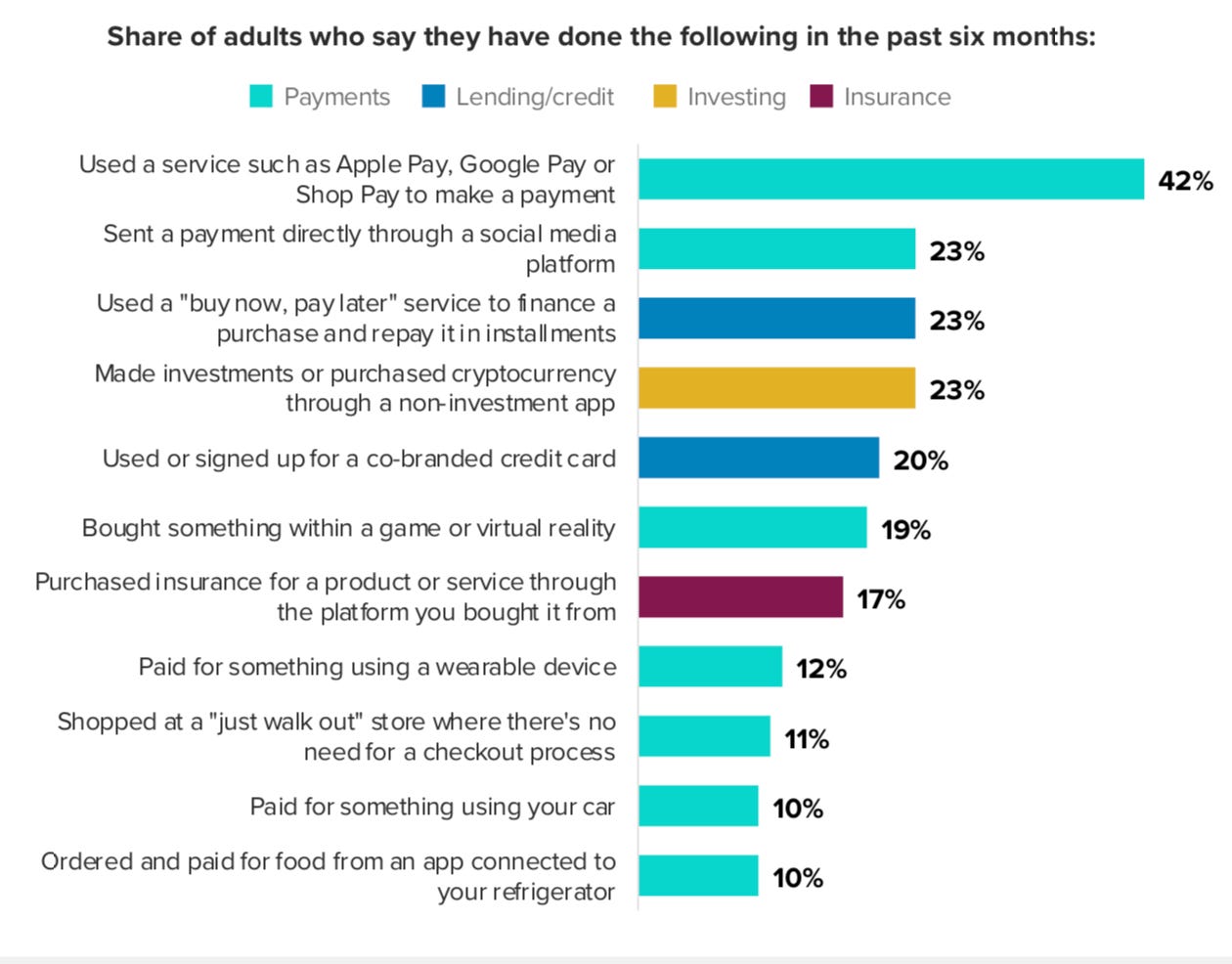

Morning Consult this week published a highly detailed report on the state of consumer banking, based on a late December 2021 survey of 2200 American adults. Much here caught FIN’s eye, including that 24% said they or someone in their household owns cryptocurrency. But the most surprising element involved the quiet popularity of “embedded finance,” the ways that people pay for things outside traditional, formal methods. This chart brings it home:

The top few bars make sense, but as the chart goes down, wait: 10% of American adults have paid for something using their car? Aside from drive-thru Dairy Queen with a debit card, FIN wouldn’t even know how to do that. Same for the fridge. Perhaps the numbers are crazy off, but they suggest that sooner or later all this Internet-of-Things, embedded finance stuff will be ubiquitous.

FINvestments

🦈Number of the Week: The Bahamas-based crypto exchange FTX raised a $400 million Series C round this week, valuing the firm at a staggering $32 billion. In its last raise way back in October, FTX was worth a measly $25 billion.

🦈Latin American companies are typically required by law to issue and pay invoices electronically; in Mexico alone, 9 billion invoices were processed in 2020. This week, Flexio, a Mexican-based company that automates bill payments and processing, raised $3 million in a seed round led by Costanoa Ventures. The company launched last year and plans to quadruple in size in the first half of this year.

🦈The London-based money transfer firm Zepz startled the UK fintech community this week when Bloomberg reported it will go public on the US market. The IPO is supposed to value the company at $6 billion.